Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi

on Barjeel Art Foundation,

showcasing Art to Unite People,

adding to the History of Art and on the

Power of Technology for the Arts

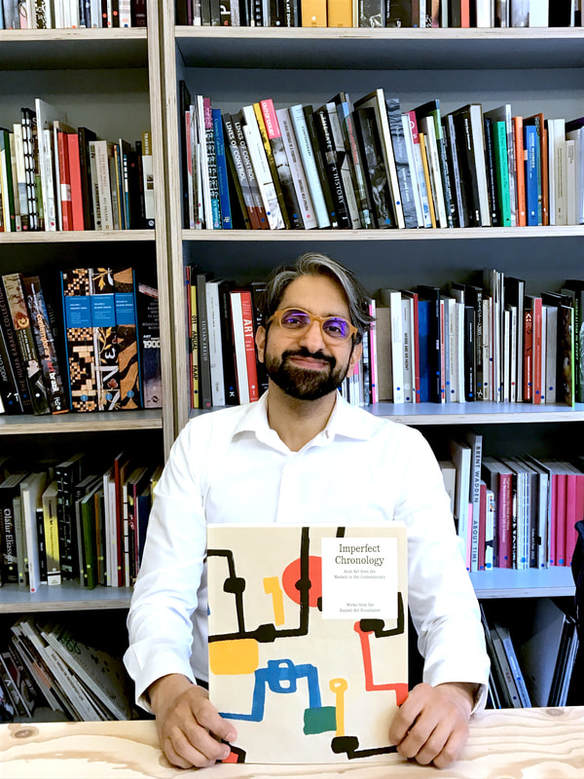

Sultan Al Qassemi in the Library of the Delfina Foundation in London with the book "Imperfect Chronology": artworks of the Barjeel Art Foundation.

Through his foundation, the Barjeel Art Foundation, he has opened up his art collection to all, for people to be inspired by art, and in turn breath out inspiration and hopefully empathy towards humanity.

With devotion he’s showing that art transcends borders and creates bridges that highlight our similarities.

Armed with paintings and sculptures, his quest is also to complement the History of Art as we know it.

I had the pleasure to talk with Sultan Al Qassemi in the beautiful library of the Delfina Foundation where our conversation started on his first discoveries of art leading to how technology and social media have paved the way to give artists a platform...

As a teenager I was always interested in culture and education. Growing up in Sharjah there was the Sharjah

International Book Fair that had been established in 1977 and all my life I grew up surrounded by books and culture as my mum was a teacher, my father was a big fan of reading, my elder brother too read a lot and we had a lot of books in our house.

Then I went to France and there I started going to exhibitions, including ones on Modern Art, Impressionist and Classical Art. I think during my teenage years in the 1990s in Paris between the age of 16 and 20 is when my love for art blossomed.

You established the Barjeel Art Foundation, how did that come about and why was it important for you to start?

I started buying art in around 2001/2002; a few years later I remember Blackberry had started doing Blackberry services and they had a messenger device called BBM, I used to take pictures and use that device to send to friends artworks I liked or bought. As I was doing that, a lot of people were asking me where they could see these artworks and was I showing them anywhere. I started to realise that there was no space, at least in the UAE, to show a private collection-this is of course was in the mid 2000-so I worked on that, and then finally in 2009, The Sharjah Government gave me a space, which is a space we still have until May 2018 before I give it back and we move on to the second chapter of the foundation’s existence.

Sounds exciting, can we talk about the second chapter or not yet?

Yes we can talk about it now.

What’s the second chapter?

Over the past almost decade we have been showing exhibitions in the foundation and internationally. I am very grateful to the government.

The collection had a lot of exposure internationally and I still wanted to base it in the UAE, however we outgrew our current space.

In January 2018, we signed an agreement for a 5 year lease for one of the spaces in the Sharjah Art Museum, they have been very generous with us, it’s a nominal fee for the lease and I am very grateful to them. It’s a massive space of 800 square metres, so it’s at least 4 times bigger than our current space allows us to have, with at least a 100 works on display at the same time and it is a long term display. So rather than temporary exhibitions of a couple of months or a few weeks, we are looking at a 5 year long exhibition that I feel will give people the time to establish some kind of relationship with the artworks.

It is important for me to have the works on display somewhere so that people can view them.

I tell my colleagues that ideally I would like every single work out of storage and onto walls or spaces but that’s very difficult when you are looking at a collection of a 1000 and plus works; which brings me to a different point, that of which I am trying to consolidate the collection and tighten it up. We are looking at de-accessing some of the work, precisely so that we can tighten it up, as some of the works are repetitive or from similar eras of an artist’s career. I am trying to see if we can differentiate the collection to have less but stronger pieces.

When it came time to choosing where to have the collection I was really scouting possible locations, but for a number of reasons my heart was always in Sharjah.

I would have been as happy having the works on display long term in Beirut or in Amman, or in Cairo or anywhere that is accessible to people, as long as the space is accessible, as long as it’s possible for a large number of people to visit.

I realise that not everybody can visit because it’s expensive to travel and there are other restrictions such as acquiring a visa to come to the UAE. But ultimately Sharjah made the most sense, we had a relationship with the Museum, in 2016 we mounted an exhibition with them, we’ve loaned them a few artworks, so there is this history with them and at the same time I feel that Sharjah in a sense is the underdog, a lot of other cities in the region have so much money and have so much accessibility to art. Even cities that are not rich like Beirut for instance, there are people who are basing their collections there, which is wonderful for Beirut so I really thought I want to give Sharjah a sort of a leg up and make sure that the collection is there. But I would have really been honestly as happy if the collection was in Casablanca or in Tunisia, hopefully one day in Bagdad on a long term bases, I would be more than happy for that.

The idea is not to supplement but complement the Eurocentric Modern Art narrative and scholarship. The idea is we recognise and we acknowledge this great wealth of art that has come from the West but there is also a great wealth of art that has come from the East whether as you said, it’s Iran, or Pakistan or India, East Asia, Africa or Latin America, the Global South some may call it, I think has been overlooked and we probably need another two or three decades of continuing to research, exhibit or promote art from these regions in order for us to arrive at a more balanced world view of Modern Art.

One artist for sure to know about, is Marwan. Marwan was a Syrian artist who lived in Berlin and unfortunately passed away in 2016 at the age of 82. He was an artist who obtained a great deal of acclaim in Germany and in Europe but wasn’t as known as he should have been in other parts of the West or other parts of the Middle East. He’s an artist that we have collected in depth, we have over a dozen works by him from various eras, we have also mounted his only exhibition ever in his lifetime in the Gulf and have invested in scholarships and promoted his work. The BBC just ran a program of his work. A documentary on unknown Modernists or overlooked Modernists of the world and Marwan was one of these artists.

The artist Saloua Raouda Choucair is also someone to know about and look up about. We have a couple of important works from her, one is a painting from the 1960s, and the other a sculpture. We have a number of Modernist artworks, the collection also includes Contemporary Art, but I feel that we need to also highlight Modern Art, many of the artists are no longer with us so we have to play a role in promoting their work, at least do it on their behalf.

HEAD by Marwan 1976 Medium: Painting Exhibition: The Short Century, Topographies of the Soul, A Century in Flux

Work from the Barjeel Art Foundation

https://www.barjeelartfoundation.org/collection/marwan-kassab-bachi-head/

The Last Sound by Ibrahim El-Salahi, (Oil on Canvas) 1964 from The Barjeel Art Foundation

www.barjeelartfoundation.org/collection/last-sound-ibrahim-salahi/

Oh definitely it holds a lot of power. I always think of this example from a few years ago, when Barak Obama visited Brazil for a meeting with the then president Dilma Rousseff, she had asked for a loan of the artwork by the Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral from an Argentinian collector who holds his collection in Buenos Aires.

So for the president of a country to request from the collector of a different country an artwork to show off their best art even-though it is held in a different country, gives us an example of how art and art collections can be important or how the power of art works and what art diplomacy is.

Another example is Mathaf in Qatar, Mathaf is an Arab Museum of Modern Art, they also have non Arab art, but in its majority it is a collection of Arab art. They have some of the most important works from Iraq and Iraqi artists that are inaccessible in Iraq, you can only view them in some places in the world, and Mathaf is one of those most important places to see this collection, so for example that gives a lot of leeway and leverage to Doha.

About a year and a half ago, we mounted an exhibition in Tehran, showing a collection of Modern Art. It was the first Modern Art exhibition in Iran from the Arab world, and we made sure as much as possible to try and take art from across the Arab world. We were limited to 40 paintings, because of limited space and budgetary constraints but we really did try to include as much as we could a diversity of artists, so we had a Jewish Egyptian artist, a Amazigh Moroccan artist, an Armenian Lebanese artist, a Turkmen Arab artist and a Kurdish artist, a Bahraini, Arabs of Persian origin, Christian Arabs, Shia Arabs, Muslim Arabs, we tried to make it as diverse as possible, but it’s also very difficult because there is no way that you can represent the width and the breadth of the Arab world in 40 paintings. For example we didn’t have works from Libya, we didn’t have works from Yemen, I don’t think we took works from Sudan to that exhibition, Oman wasn’t represented there, so how do you choose? I have this collectors guilt with myself if a particular region or country is not represented, I guess this is how I feel sometimes.

It is great to see art being placed with the idea of trying to unify people

Well I think that there are artists who painted works that we would not have known the significance of or the messages behind them, had it not been for some of their friends or some scholars or even some of the artists acquaintances who relayed to us stories once the artist passed away, of what an artwork is about. So it’s very important to document this and it’s also important to note that an artist can just be in the mood to paint a certain abstract work and she or he, is not trying to reference the void of politics in their respective country. Sometimes we do have a tendency I think to overanalyse an artwork, but the more scholarship there is, the better for us in our part of the world, whether it’s the Arab world, Iran or South Asia, this is something where we need to catch up with the rest of the world and yet also I think, we need to leave a little bit to the imagination.

I can give you an example from our Barjeel collection, when I started it 15 or 16 years ago, it was more male dominated, it was more dominated by Contemporary Art, but now it’s gender balanced. I have many more female artists which I am very happy about, and we have more Modern Art versus Contemporary Art.

About 20 years ago, the role of women was highlighted in an exhibition in the US, that Salwa Mikdadi curated. It was a travelling exhibition called Forces of Change: artists of the Arab world.

She toured the exhibition taking it to Washington and other parts of the US. It’s one of the instances that women art was sort of put at the forefront.

Although I am not a big fan of compartmentalising male and female art, as I think they complement each other rather than supplement each other, but there needs to be more attention paid to women artists. At this moment in time, a lot of the scholars are women, such as Salwa Mikdadi and Nada Shabout, furthermore, so many of the non Arab art scholars are also women. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie published an important essay on Inji Aflatoun, so we are seeing that women are researching women artists and we are seeing the importance of artists like Inji Aflatoun, Effat Naghi, Gazbia Sirry, Kamala Ishaq, the sudanese artist who was shown in Sharjah recently, and Saloua Raouda Choucair whom the Tate had on an exhibition of her work. Many other women artists are getting a little bit of their share of recognition, I think there needs to be much much more, but they are getting a little bit of their share of acknowledgment in regards to scholarship and being highlighted in exhibitions.

Prisoners by Inji Afflatoun (Oil on Canvas) 1957 from the Barjeel Art Foundation

www.barjeelartfoundation.org/collection/prisoners/

For instance, one of the exhibitions in Sharjah is “Beloved Bodies” which is a title that may be a little risky or controversial in the region. How do you feel about pushing boundaries?

Well we have gotten away with some artworks the last few years which I cannot think of displaying now. We had artworks that depicted issues that are for some people problematic, not for me, I don’t see anything being problematic, and I am very fortunate that things were accepted in that sense. But I would say that when a collection is lesser known, you get away with much more than when it is a more recognised collection because people then start looking in detail and reading about the show. This is what I feel and what I’ve noticed.

It seems like the public spaces that were regained with all the graffiti art have been lost-what are your thoughts since then?

I think with regards to graffiti, the nature of it, is that it disappears, the nature of graffiti is ephemeral. So we shouldn’t mourn the loss of graffiti, we are very fortunate to have photography now, we can just photograph it and recall what things were. But public walls are supposed to be painted over and over and over again, that’s why it is graffiti.

I think since those days, there has been a lot of positive development and a lot of negative development. In terms of positive development, there are many more people who recognise artworks, there are many people who recognise artists thanks to social media, at the same we’ve seen a lot of artists because of the Arab Spring or the tensions since then, that have had to leave their respective countries and move to settle in other countries.

But I feel like the last couple of years have been a roller coaster ride but then the entire history of Middle East has been a roller coaster ride.

I was a fellow from 2014 to 2016 at the MIT Media Lab and over there we tried to find the nexus between the academic world and the practical world. We tried to plug in the holes or the gaps that exist in these two different spheres.

In the Lab itself there were people who worked for Twitter and who worked for other social media organisations and there is no doubt that new media whether it is social media or other forms of media can play a very important role.

If you think for example of what Google Art Project has been doing with photographing and documenting artworks and with the ultra high resolution gigapixel allowing people to zoom into an artwork further in and in, looking and going into the details that were not available to the naked eye for centuries, you can start seeing that now, even seeing the mistakes made by artists on their artworks that may stem from centuries ago.

We have also seen that art has become more accessible, more fun and less elitist, for instance, a few weeks ago, Google Art had released or announced some kind of facility, where if you take a picture of yourself and upload it you can then find an artwork in the world that resembles you. Millions of people started taking their pictures and they started learning about art and learning about museums and institutions that they may have never had heard of. So art has a way of democratising things and social media and technology have a way of democratising the art collections. Again due to prohibitions like visas, cost of travel, we can’t be everywhere, we can’t now just up and leave and go to the National Gallery in Sydney Australia or to Brazil, I would love to, but I am not able to always be in Brazil, Hong Kong, Australia and Canada, it’s very difficult and it’s very expensive.

Furthermore, most museums only show 2 to 3 % of their collections at any one point and some museums show much less, so at least now with the documentation, with many works being made available online, you can see the artworks that may not be on display, you can study them, make them available to students and academics, and this is no longer just available for one or two months every decade in an exhibition, now it is available all the time, so now the exception has become the lack of availability rather than the exception being the availability of the artwork. This is what has happened in the last few years.

This is a term that was developed by Professor Joseph Nye, an American professor who is now at Harvard who I had the honour of working with for two years during my time at the Global Commission for Internet Governance.

The idea of Soft Power is that there are other levers of influence that are none military, so they include finance, they include diplomacy, they include culture, and in our world culture has an important role to play, because what politics and military has done is divide people, art has a way of reuniting people and bringing them back together.

Politics can sometimes seem to highlight differences between people, for instance pointing towards a person’s sect or ethnic group, and highlighting these issues in a way as though they are negatives, I think art has a way of bringing all people together no matter what their identity; stating something like well this is what we all believe in, this is our common identity.

We can have a common identity through art and togetherness and we can also respect the plurality of identities.

I always say that we have to stop referring to the Middle East or the Arab world in singular terms, because we are really a plurality, we are not a Middle Eastern culture, we are Middle Eastern cultures we are not an Arab culture, we are Arab cultures, we have people who are from all different backgrounds, and all different ethnicities and minorities. And all form part of the art world, there are Jewish Egyptian artists or Armenian Lebanese artists or Amazigh Morrocan artists, these are all part of the multitude of identities that we have within the Arab world, and within the Middle East and North Africa. So I think art has a way of showing you the positives where the politics tends to in general highlight the negatives.

In some ways I believe in competition, so I believe that others should put more works online, there needs to be more. If we are beating you in this field then we should not be beating you, we want to race people, we need to have a positive race, a race of ideas, a race of art. That’s what we need, we need to stop looking at negative races and we need to look at positive races, who can put more art, who can put more culture online—we all need to compete with each other with good things. And the good news is that if we do that then we are all winners.

If we put so much art, everyone at one point is an artist, do you think there is that danger? Or does that not matter at all?

Just like in the music world where you have a lot of people releasing their own music, putting it on sound cloud, somebody at some point will be discovered, at some moment, the right person will listen to the right track at the right time and that tool of technology will have enabled them to be highlighted and maybe the person ends up getting a recording contract.

I think ultimately, that the more art we can share, the better, and then people can pick and choose what they want to see. Art is a very subjective issue, there are some artworks that you might find appealing that I may disagree with and vice versa, so it is good that there is the availability for all to showcase their art.

I like painting and sculpture; but it doesn’t mean that I don’t like video.

I have my certain peculiar preferences: Modern 60s Art. In general I love 1960s work, I don’t know why but I can tell when something is from the 1960s. I can almost always tell, I don’t know what it is, but my heart almost skips a beat and I want to walk closer to the artwork. I am drawn to 60s artworks whether they are Middle Eastern or non Middle Eastern artists, either for instance by Parviz Tanavoli from Iran or Wifredo Lam from Cuba.

That is a decade that is closest to my heart.

Just like art, architecture is another activity I am passionate about. I am working on a book that documents the modern architecture of Sharjah over the last half century.

During my time at the Delfina residency, I asked them if I could create a symposium that celebrates Middle Eastern architecture, highlighting the architecture of the Gulf States, looking at the 6 GCC countries as well as Iran and Iraq. We invited 11 scholars and practitioners, and even hobbyist too—one of our speakers was a dentist who researches architecture in Iraq. The symposium was so over booked and popular that we had to move it out of Delfina to a space that could accommodate us. It was great to see that the subject interested so many.

The architecture element really appeals to me. There are facets of the Middle East that haven’t been so much highlighted, mostly what we have is politics and then some music which is good but there’s isn’t enough about film, there’s not enough about architecture and still not enough about art. It’s about expanding the discourse on architecture and the Middle East.

Architecture is really interesting; in Lebanon for instance, many are fighting to preserve the old buildings, but some want to destroy them and build high rises, and then there’s a gratitude to some restaurant owners that buy old houses to transform them into restaurants, because at least then that preserves the old architecture

Many apply the idea that if you knock them down, build a skyscraper you then can sell apartments instead of preserving a three storey 1960s building. And yet there is so much value in preserving old buildings and celebrating them, which in turn doesn’t mean there can’t be new buildings, but it is about balancing things, preserving history and moving forward.

There should be an arena to discuss architecture and its meaning.

I think this relates to one of the other questions you asked: the importance of social media.

Artworks should be available online, people need to be able to find you and see your work online.

I think we have to take advantage of the tools that are available to us in the 21st Century in 2018.

At the same time read twice as much as you produce. One issue we have with Middle Eastern artists is that the works have started to look quite similar to each other and we need to make sure that the artists take some time to read and not just paint, because it is through research that you come up with ideas. Ideas arise through educating yourself; not just through reading, it could be by listening to pod casts or watching documentaries, whichever way a person can gain more knowledge, because the more knowledge you have the better curator, art activist or artist you are going to be. As my friend says you have two ears and one mouth, so you should learn more, take in more through your ears and eyes and say less.

I think that we really need to put more effort by absorbing and learning more about the world around us; and not just the Contemporary world, but the Modern world, the historical one, the classical world and so forth.

By learning about and around the arts, if we all learn more, can art yield peace?

I don’t think that art will bring about peace, but I think that without culture it will be a very strenuous peace, as culture has its way of uniting people.

For instance, the Lebanese during the civil war all agreed on the importance of preserving the National Museum. I am not sure if it was ever even targeted on purpose—it might have been targeted by mistake, but nobody went after it because people are proud of their culture.

Another example is during the uprising in Egypt, some people were against the government and some people for the government, yet Egyptians formed a human chain to protect their National Museum.

There are a lot of examples that we have in the Middle East, North Africa, the Arab world and other parts of the region, were people can disagree on many things on their politics or on sectarian issues and it’s really terrible but they ultimately can agree on their culture.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi is the founder of the Barjeel Art Foundation, an independent initiative established to contribute to the intellectual development of the art scene in the Arab region by building a prominent and publicly accessible art collection in the United Arab Emirates.

In addition to building an informative database of artists, the foundation is seeking to develop an educational programme that both understands and involves the local community.

Sultan Al Qassemi is a United Arab Emirates-based columnist whose articles have appeared in The Financial Times, The Independent, The Guardian, The Huffington Post, The New York Times Room for Debate, Foreign Policy, Open Democracy, and The Globe and Mail, as well as other notable publications.

He is also a prominent commentator on Arab affairs on Twitter. Rising in prominence during the Arab Spring, his tweets became a major news source, rivaling the major news networks at the time, until TIME magazine listed him in the “140 Best Twitter Feeds of 2011.”

He was an MIT Media Lab Director’s Fellow from 2014-2016, and in the Spring of 2017 was a practitioner in residence at the Hagop Kevorkian Center of Near East Studies at New York University, where he offered a special course on Politics of Middle Eastern Art

Sultan continues to write and tweet about the Arab world from his home in Sharjah, and also while giving lectures internationally.

http://www.barjeelartfoundation.or

www.sultanalqassemi.com