Michael Landy on

Art, Society, Politics,

and

"Breaking News"

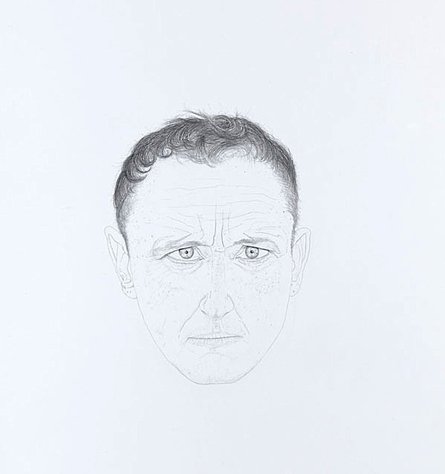

Michael Landy, Self-Portrait #4

Michael Landy fellow at the Royal Academy is one of those artists that through his work leaves an impact wherever he goes and whatever he does.

His work covers the notion of value and the concept of consumerism, as well as looking to the self and to society.

He passionately cares about society, his students at the Royal Academy and where the world is headed. With a humanitarian heart and outlook, he conquers political and social subjects through his art and creative mind.

Michael Landy’s work include the infamous “Break Down” in 2001, where he landfilled all of his belongings, “Acts of Kindness” a project that highlighted acts of kindness on the London underground, “Art Bin” where Landy invited people to throw their artworks in an act of ‘celebration to creative failure’, “Closing Down Sale” the artist’s reaction to London’s recession in the 1990s and “Saints Alive” kinetic sculptures reflecting paintings from the National Gallery.

Michael Landy’s art is important for society, it makes us stop, think and reflect.

His work covers the notion of value and the concept of consumerism, as well as looking to the self and to society.

He passionately cares about society, his students at the Royal Academy and where the world is headed. With a humanitarian heart and outlook, he conquers political and social subjects through his art and creative mind.

Michael Landy’s work include the infamous “Break Down” in 2001, where he landfilled all of his belongings, “Acts of Kindness” a project that highlighted acts of kindness on the London underground, “Art Bin” where Landy invited people to throw their artworks in an act of ‘celebration to creative failure’, “Closing Down Sale” the artist’s reaction to London’s recession in the 1990s and “Saints Alive” kinetic sculptures reflecting paintings from the National Gallery.

Michael Landy’s art is important for society, it makes us stop, think and reflect.

Did you choose art or do you think that art chose you?

Well I didn’t know what it was actually when I first started, I mean I knew that I liked to draw things, you put something in front of me and I would draw it.

It was really my way into what I have discovered is the art world.

At the beginning I really liked drawing and looking, then a grown up said I was good at it and then a teacher said I was good and then it just carried on.

I studied textiles actually, I went to Loughborough were it was basically an extension to the foundation course. I liked ready-made pattern, just repeated pattern but I had no empathy for fabric and that became a problem when I had to specialise in the following two years.

I remember on the foundation course there was someone hammering some daffodils onto a board, and I thought I come from a working class background so for me I had to get a job at the end of it, and with fine art, I just could not get my head round it. It was a much easier, a more conservative route to study textiles, because I kind of imagined that there would be some sort of job at the end of it, which obviously transpired not to be.

Ultimately in the end I decided to study fine art because my things were fine art textiles. I had enough of having to legitimise why this was a ‘textile artwork’.

So at the end I just decided to study art, and drawing was my way into it.

It’s the skill element really of it, that kind of what drew me in.

Then I tried to get into Goldsmiths a few times on the fine art course and I kept on getting turned down, eventually I got in. You could basically study what you wanted, you could be a poet, you could wonder around in pig trotters in a balaclava naked for 24 hours walking around in a circle if that’s what you wanted to do or you could do absolutely nothing at all, so you basically created the course and that’s the kind of freedom that I wanted.

Some people found it very hard, and it is hard, because you are treated like a grown up artist, you get a space and you have to pigeonhole the tutors to get to have a conversation with them. Basically you create your own course. Those who left school and went straight away to Goldsmiths found it really hard, because they were looking for some sort of structure – but that was not the course. The ethos was you create your own course, you didn’t have to specialise in anything. You could do whatever you wanted to do.

It’s probably quite different to now

Yeah it is probably very different. I mean when I left art school, there were only about 3 or 4 galleries that may have given you an exhibition.

I was called a YBA (Young British Artist) at that point. We basically decided to create the circumstance, we created our own artwork, we created the environment to show our artwork in, we found the spaces and we actually sold our own artwork as well. But something like that is not sustainable for vast amounts of time.

Art schools are very different places today – well so I am told – I think money is much more of a priority for people.

Sometimes I teach at the Royal Academy, and you talk to young people and they are like thinking or saying that as soon as they finish the course they get out of London, because they can’t afford to live in London.

When I left art school, I lived in a squat. I could live on short hand housing for £ 8 a week, you could exist for not very much and that meant you could pursue your artwork. If you are working the whole time just to pay the bill, you have no time left for your artwork, so it becomes about weighing things up.

But at the same time, London to a certain extent at the moment, sucks everybody in, whether economically or creatively. It may not always be the case, it might eventually literally price itself out and there are interesting things happening in other parts of the country. So maybe actually in the long term not being so London centric might be a good thing.

The 1997 Sensation exhibition that you were part of was quite a cult moment in the art world, how do you feel looking back now?

When you say Sensation, I don’t really feel that much part of it, unlike how I felt when we did “Freeze” with Damian Hirst, Gary Hume and Sarah Lucas. I was really very much part of that at the start back in 1988.

It was just a very different world then and you could find abandoned buildings. Damien got money to do up a space, which was in Surrey Keys and for a catalogue.

I was the driver in my beetle as I was the only one with the car basically. I had to chauffeur people around, and I used to drive round and go to the LDDC, and Damien would try to talk to people to get money and support.

Is that when you did your artwork “Market”?

That’s in 1988, so 2 Years after “Freeze”

Straight away it is political – about consumerism, I was wondering do you think the role of an artist is to highlight what is going on in society?

I think that is one of the roles. The art world itself is quite a small world, so only sometimes can you break out of that and ‘occupy’ ‘the real world’, if we can call it that. It doesn’t happen that often.

The artwork “Market” was like the beginning of everything really, so people didn’t really understand it. It really is my homage to – not a global market – but a once a week market, where I used to say that real goods exchange between real people, as opposed to a global cyber’s market. That was very early on and people didn’t really know what it was, it is basically 100 market stalls, just very humdrum, ready made crates that are stacked – nothing extraordinary – so people didn’t know what to make of it.

Well I didn’t know what it was actually when I first started, I mean I knew that I liked to draw things, you put something in front of me and I would draw it.

It was really my way into what I have discovered is the art world.

At the beginning I really liked drawing and looking, then a grown up said I was good at it and then a teacher said I was good and then it just carried on.

I studied textiles actually, I went to Loughborough were it was basically an extension to the foundation course. I liked ready-made pattern, just repeated pattern but I had no empathy for fabric and that became a problem when I had to specialise in the following two years.

I remember on the foundation course there was someone hammering some daffodils onto a board, and I thought I come from a working class background so for me I had to get a job at the end of it, and with fine art, I just could not get my head round it. It was a much easier, a more conservative route to study textiles, because I kind of imagined that there would be some sort of job at the end of it, which obviously transpired not to be.

Ultimately in the end I decided to study fine art because my things were fine art textiles. I had enough of having to legitimise why this was a ‘textile artwork’.

So at the end I just decided to study art, and drawing was my way into it.

It’s the skill element really of it, that kind of what drew me in.

Then I tried to get into Goldsmiths a few times on the fine art course and I kept on getting turned down, eventually I got in. You could basically study what you wanted, you could be a poet, you could wonder around in pig trotters in a balaclava naked for 24 hours walking around in a circle if that’s what you wanted to do or you could do absolutely nothing at all, so you basically created the course and that’s the kind of freedom that I wanted.

Some people found it very hard, and it is hard, because you are treated like a grown up artist, you get a space and you have to pigeonhole the tutors to get to have a conversation with them. Basically you create your own course. Those who left school and went straight away to Goldsmiths found it really hard, because they were looking for some sort of structure – but that was not the course. The ethos was you create your own course, you didn’t have to specialise in anything. You could do whatever you wanted to do.

It’s probably quite different to now

Yeah it is probably very different. I mean when I left art school, there were only about 3 or 4 galleries that may have given you an exhibition.

I was called a YBA (Young British Artist) at that point. We basically decided to create the circumstance, we created our own artwork, we created the environment to show our artwork in, we found the spaces and we actually sold our own artwork as well. But something like that is not sustainable for vast amounts of time.

Art schools are very different places today – well so I am told – I think money is much more of a priority for people.

Sometimes I teach at the Royal Academy, and you talk to young people and they are like thinking or saying that as soon as they finish the course they get out of London, because they can’t afford to live in London.

When I left art school, I lived in a squat. I could live on short hand housing for £ 8 a week, you could exist for not very much and that meant you could pursue your artwork. If you are working the whole time just to pay the bill, you have no time left for your artwork, so it becomes about weighing things up.

But at the same time, London to a certain extent at the moment, sucks everybody in, whether economically or creatively. It may not always be the case, it might eventually literally price itself out and there are interesting things happening in other parts of the country. So maybe actually in the long term not being so London centric might be a good thing.

The 1997 Sensation exhibition that you were part of was quite a cult moment in the art world, how do you feel looking back now?

When you say Sensation, I don’t really feel that much part of it, unlike how I felt when we did “Freeze” with Damian Hirst, Gary Hume and Sarah Lucas. I was really very much part of that at the start back in 1988.

It was just a very different world then and you could find abandoned buildings. Damien got money to do up a space, which was in Surrey Keys and for a catalogue.

I was the driver in my beetle as I was the only one with the car basically. I had to chauffeur people around, and I used to drive round and go to the LDDC, and Damien would try to talk to people to get money and support.

Is that when you did your artwork “Market”?

That’s in 1988, so 2 Years after “Freeze”

Straight away it is political – about consumerism, I was wondering do you think the role of an artist is to highlight what is going on in society?

I think that is one of the roles. The art world itself is quite a small world, so only sometimes can you break out of that and ‘occupy’ ‘the real world’, if we can call it that. It doesn’t happen that often.

The artwork “Market” was like the beginning of everything really, so people didn’t really understand it. It really is my homage to – not a global market – but a once a week market, where I used to say that real goods exchange between real people, as opposed to a global cyber’s market. That was very early on and people didn’t really know what it was, it is basically 100 market stalls, just very humdrum, ready made crates that are stacked – nothing extraordinary – so people didn’t know what to make of it.

Michael Landy, Market, 1990. Installation view, Building One, London

Do you think art can be a good tool to explain politics? Does it help ensure that politics is covered with different perspectives or different points of view?

It can look at different points, but its audience is a very small audience on a whole I think, and quite a lot of the time you are preaching to the converted.

Like I said you can invade a whole new different territory, because artists can turn things on their head. I mean the whole Brexit thing is an interesting phenomenon and what kind of country we are, whether we are an inward looking country or whether we are an outward looking country. Living in the art world bubble I kind of knew that everyone I talked to or like 99% were wanting to stay in, but when you start to look at other parts of the country, it’s a different story.

I was chatting to a business man who has a business up in Stoke and he said everyone had ‘Leave’ signs everywhere and so when you hear something like that, you then know you are living in a cocoon bubble.

And sometimes you step outside that.

Well, that’s what I thought after Brexit actually, I thought, I don’t obviously know my own country, I don’t know where I am living anymore. But that’s all basically or a lot of it, is the stuff we haven’t dealt with from like 30 years ago. Like when I did the artwork “Scrapheap Services”, a lot of people were thrown on the scrappy back in the late 80s, 90s that form of manufacturing, suddenly they were no longer existent. We’ve forgotten about it really and it came back to bite people on the bums.

Is that what your artwork “Breaking News” is about?

It’s partly that because “Breaking News” is quite literally about the news in some respects, but it’s also partly self referential about some of the things I’ve created in the past but sometimes it can just be about what’s happening right now.

It can look at different points, but its audience is a very small audience on a whole I think, and quite a lot of the time you are preaching to the converted.

Like I said you can invade a whole new different territory, because artists can turn things on their head. I mean the whole Brexit thing is an interesting phenomenon and what kind of country we are, whether we are an inward looking country or whether we are an outward looking country. Living in the art world bubble I kind of knew that everyone I talked to or like 99% were wanting to stay in, but when you start to look at other parts of the country, it’s a different story.

I was chatting to a business man who has a business up in Stoke and he said everyone had ‘Leave’ signs everywhere and so when you hear something like that, you then know you are living in a cocoon bubble.

And sometimes you step outside that.

Well, that’s what I thought after Brexit actually, I thought, I don’t obviously know my own country, I don’t know where I am living anymore. But that’s all basically or a lot of it, is the stuff we haven’t dealt with from like 30 years ago. Like when I did the artwork “Scrapheap Services”, a lot of people were thrown on the scrappy back in the late 80s, 90s that form of manufacturing, suddenly they were no longer existent. We’ve forgotten about it really and it came back to bite people on the bums.

Is that what your artwork “Breaking News” is about?

It’s partly that because “Breaking News” is quite literally about the news in some respects, but it’s also partly self referential about some of the things I’ve created in the past but sometimes it can just be about what’s happening right now.

Michael Landy, Breaking News, 2015. Installation view, Michael Landy Studio

You chose to do it in red and white is there a reason for that?

It’s like danger signs.

Red and white itself catches people’s eye as well, that’s obviously why they use it as danger signs.

I have made about 700 to 800 hundred “Breaking News” drawings all together.

It is only a small catchment of the artwork that you saw at Frieze. I had a show in Munich with “Breaking News”, which was more to do with the Greek - German dialogue.

Is that why there are lots of German words?

No that’s to do with what was said in regards to Brexit, I can’t remember if it was Der Spiegel or another German tabloid that reported it, but it was said that, if we stayed in the EU, then they wouldn’t keep going on about the 1966 world cup final where the ball didn’t go over the line, so they’d let us win that one, they wouldn’t contest it any longer.

Well I guess now they can contest it…

Well yeah they can contest away…

Do you also feel that by creating the pieces for your artwork “Breaking News” as tabloids in torn pieces, that it is a reaction to how we are fed information or how the ‘other’ is portrayed?

It’s partly a play on tabloid vernacular.

They call them red tops as well, which is ironic.

Obviously, tabloids had much more power back in the 70s and 80s than they do have now, so I don’t know how young people consume their news.

Probably through social media

It’s probably become more about the headlines

Maybe I wasn’t when I was young interested in the news either to be honest.

I probably thought, what’s it got to do with me?

But most of your art is political and even your artworks back from the 1990s are is still so relevant, because in a way the world is still going through similar issues, I mean we have moved on with technology, but there are still many people struggling and more and more of a gap between rich and poor. Your art comes out of the bubble you’ve talked about, comes out of the art world and communicates with people, and so I wonder if that’s also why you chose with “Breaking News” to go into what people pick up everyday, which is a newspaper, I mean for instance, in the tube everyday, there’s a free Metro paper

Yes headlines are picked up on. There’s one that I made of Margaret Thatcher holding up the sign she had held up back in the 1980s saying “let the rich get richer”. You would never see a politician hold up a sign like that anymore. At that point it was all about the trickle down effect, which ultimately didn’t work, so I kind of track things.

I basically left school in 1979 when Margaret Thatcher came to power and so I think that partly creates me as an artist in a sense.

At Goldsmiths people weren’t interested in politics, not really.

Also it felt a bit odd switching afterwards to drawing because I didn’t draw at art college, I did other things at art college, because I thought no one else is drawing, so I’m not going to draw, and so that came up afterwards actually. I think because I always knew value and worth and what value and worth society gives to things and what things we overlook, what things we ignore and obviously one wants to know why is that. We are good at it in this country anyway at just writing things off, and putting them to one side, and that’s why, what’s interesting about Brexit, is that those people came back to haunt us, those people that were written off, that were ignored for a long time, ignored for the last 20 or 30 years came back to bite the establishment on the bum.

I guess that’s why maybe art should be more looked at, should be more readily available, highlighting things maybe the government should have looked at and listened to.

But they had their own internal affairs, you know that was Tory politics…

It’s like danger signs.

Red and white itself catches people’s eye as well, that’s obviously why they use it as danger signs.

I have made about 700 to 800 hundred “Breaking News” drawings all together.

It is only a small catchment of the artwork that you saw at Frieze. I had a show in Munich with “Breaking News”, which was more to do with the Greek - German dialogue.

Is that why there are lots of German words?

No that’s to do with what was said in regards to Brexit, I can’t remember if it was Der Spiegel or another German tabloid that reported it, but it was said that, if we stayed in the EU, then they wouldn’t keep going on about the 1966 world cup final where the ball didn’t go over the line, so they’d let us win that one, they wouldn’t contest it any longer.

Well I guess now they can contest it…

Well yeah they can contest away…

Do you also feel that by creating the pieces for your artwork “Breaking News” as tabloids in torn pieces, that it is a reaction to how we are fed information or how the ‘other’ is portrayed?

It’s partly a play on tabloid vernacular.

They call them red tops as well, which is ironic.

Obviously, tabloids had much more power back in the 70s and 80s than they do have now, so I don’t know how young people consume their news.

Probably through social media

It’s probably become more about the headlines

Maybe I wasn’t when I was young interested in the news either to be honest.

I probably thought, what’s it got to do with me?

But most of your art is political and even your artworks back from the 1990s are is still so relevant, because in a way the world is still going through similar issues, I mean we have moved on with technology, but there are still many people struggling and more and more of a gap between rich and poor. Your art comes out of the bubble you’ve talked about, comes out of the art world and communicates with people, and so I wonder if that’s also why you chose with “Breaking News” to go into what people pick up everyday, which is a newspaper, I mean for instance, in the tube everyday, there’s a free Metro paper

Yes headlines are picked up on. There’s one that I made of Margaret Thatcher holding up the sign she had held up back in the 1980s saying “let the rich get richer”. You would never see a politician hold up a sign like that anymore. At that point it was all about the trickle down effect, which ultimately didn’t work, so I kind of track things.

I basically left school in 1979 when Margaret Thatcher came to power and so I think that partly creates me as an artist in a sense.

At Goldsmiths people weren’t interested in politics, not really.

Also it felt a bit odd switching afterwards to drawing because I didn’t draw at art college, I did other things at art college, because I thought no one else is drawing, so I’m not going to draw, and so that came up afterwards actually. I think because I always knew value and worth and what value and worth society gives to things and what things we overlook, what things we ignore and obviously one wants to know why is that. We are good at it in this country anyway at just writing things off, and putting them to one side, and that’s why, what’s interesting about Brexit, is that those people came back to haunt us, those people that were written off, that were ignored for a long time, ignored for the last 20 or 30 years came back to bite the establishment on the bum.

I guess that’s why maybe art should be more looked at, should be more readily available, highlighting things maybe the government should have looked at and listened to.

But they had their own internal affairs, you know that was Tory politics…

Michael Landy, Breaking News, 2015. Installation view, Michael Landy Studio

How does it feel to be elected as a fellow to the RA?

Well, actually the RA think I am dead. When you are an RA you get these letters through the post, basically it’s like dead man shoes, when an RA dies, you take their place, you get a phone call, asking whether you would like to be an RA, and I said yes, but that’s only because Tracey Emin asked me and I was too frightened to say no! There’s only like 70 RA’s at any one point in time.

I made this art work which is also a “Breaking News” work where I falsify the president’s signature, because you know, you get this letter saying that such and such has died and so I did me basically, I pretended I’m dead.

So when you turn up they think you are a ghost!

They thought, gone gone…

I think artists on the whole aren’t bureaucrats, and it’s very bureaucratic, so I tried not to go, even though I love the RA because it’s a very British Institution.

The first time I was there, I was there for about 2 or 3 hours and they talked about reintroducing a ball machine that they used to have to nominate the artist, a hollowed out piece of wood that you put marbles either side of. It was always a male artist at that point. That went on for a while which is alright in the 17th century when there was time.

Don’t tell them I’ve come back.

I won’t, I’ll write interview with ghost

Even though the president does know.

So do you think there’s a lot of talk about art being non-elitist, but actually it still kind of is?

I think it is pretty much, I think it still is, it’s a kind of microcosm really, even though it’s a bigger world then it was when I left art college it still is quite small, but I think artists do have a role and I think they still look at things, because they don’t need your votes.

There are now more blurred boundaries in art with other disciplines, in a sense also, there are trends in art, but art feels like it’s less instant, whereas something like fashion, it can be a really fast industry

I like breaking and blurring, that’s good.

Fashion is about turn over and about ideas, but that’s a fashion cycle in a way.

I guess being a consumer is like that, isn’t it.

I was chatting to this chap about photography and he said to me, we look at more images in a morning than an 18th century peasant would have seen in their whole lives.

People look at images or Instagram and that’s our realm in a sense.

The world is a much more visual place. When I was at art college, the word was much more important than the visuals and it was kind of maybe slightly dismissed but since we live in a much more visual world now, people are obviously much more sophisticated at looking at visuals.

I don’t know what you think of this, but I feel that with art, people have a need to understand it, rather than enjoy it, whereas with fashion, even though there are more people interested with what lies behind a garment, they don’t need to, they could just wear it and enjoy it straight away

Yeah because they have an immediate relationship with it, as with art, it doesn’t give itself up straight away.

You can’t consume it in that way, you got to maybe know something about the artist, or that’s why art fairs are interesting because quite a lot of the time you haven’t got the artist present, so all you have is the artwork and then obviously you have to look at it with whatever knowledge you bring to it, with all the vast things you have seen before. That’s also partly why people find it intimidating as well. So to an extent, it will always be something slightly elusive and that’s why it will never be completely mainstream.

What is an artist’s day like and anything you would want to do?

I was born in London and I think now, I wish I’d travelled more, I wish I’d seen more things – I can still do that though.

For me I’m in my own world – a lot of artists are kind of hermits. I spend a lot of time by myself - not just drawing – but I don’t have assistants so it’s just me and then if I create something, I get people to help me.

What do you think about having art assistants, I always wonder about that, as in if it’s an assistant that painted an artwork, it is it the artist’s art?

Yes Raphael did that, it’s nothing new.

That’s why they make prints, if you wanted to get those prints into a wider world, they had to find a way of duplications, and obviously the more art one makes, the more one would see it in Europe and beyond, so I mean artists like Warhol and others, just worked out that, that you would have to do it on an industrial scale.

But that’s not what I’m about, but that’s just the idea of it.

Well, actually the RA think I am dead. When you are an RA you get these letters through the post, basically it’s like dead man shoes, when an RA dies, you take their place, you get a phone call, asking whether you would like to be an RA, and I said yes, but that’s only because Tracey Emin asked me and I was too frightened to say no! There’s only like 70 RA’s at any one point in time.

I made this art work which is also a “Breaking News” work where I falsify the president’s signature, because you know, you get this letter saying that such and such has died and so I did me basically, I pretended I’m dead.

So when you turn up they think you are a ghost!

They thought, gone gone…

I think artists on the whole aren’t bureaucrats, and it’s very bureaucratic, so I tried not to go, even though I love the RA because it’s a very British Institution.

The first time I was there, I was there for about 2 or 3 hours and they talked about reintroducing a ball machine that they used to have to nominate the artist, a hollowed out piece of wood that you put marbles either side of. It was always a male artist at that point. That went on for a while which is alright in the 17th century when there was time.

Don’t tell them I’ve come back.

I won’t, I’ll write interview with ghost

Even though the president does know.

So do you think there’s a lot of talk about art being non-elitist, but actually it still kind of is?

I think it is pretty much, I think it still is, it’s a kind of microcosm really, even though it’s a bigger world then it was when I left art college it still is quite small, but I think artists do have a role and I think they still look at things, because they don’t need your votes.

There are now more blurred boundaries in art with other disciplines, in a sense also, there are trends in art, but art feels like it’s less instant, whereas something like fashion, it can be a really fast industry

I like breaking and blurring, that’s good.

Fashion is about turn over and about ideas, but that’s a fashion cycle in a way.

I guess being a consumer is like that, isn’t it.

I was chatting to this chap about photography and he said to me, we look at more images in a morning than an 18th century peasant would have seen in their whole lives.

People look at images or Instagram and that’s our realm in a sense.

The world is a much more visual place. When I was at art college, the word was much more important than the visuals and it was kind of maybe slightly dismissed but since we live in a much more visual world now, people are obviously much more sophisticated at looking at visuals.

I don’t know what you think of this, but I feel that with art, people have a need to understand it, rather than enjoy it, whereas with fashion, even though there are more people interested with what lies behind a garment, they don’t need to, they could just wear it and enjoy it straight away

Yeah because they have an immediate relationship with it, as with art, it doesn’t give itself up straight away.

You can’t consume it in that way, you got to maybe know something about the artist, or that’s why art fairs are interesting because quite a lot of the time you haven’t got the artist present, so all you have is the artwork and then obviously you have to look at it with whatever knowledge you bring to it, with all the vast things you have seen before. That’s also partly why people find it intimidating as well. So to an extent, it will always be something slightly elusive and that’s why it will never be completely mainstream.

What is an artist’s day like and anything you would want to do?

I was born in London and I think now, I wish I’d travelled more, I wish I’d seen more things – I can still do that though.

For me I’m in my own world – a lot of artists are kind of hermits. I spend a lot of time by myself - not just drawing – but I don’t have assistants so it’s just me and then if I create something, I get people to help me.

What do you think about having art assistants, I always wonder about that, as in if it’s an assistant that painted an artwork, it is it the artist’s art?

Yes Raphael did that, it’s nothing new.

That’s why they make prints, if you wanted to get those prints into a wider world, they had to find a way of duplications, and obviously the more art one makes, the more one would see it in Europe and beyond, so I mean artists like Warhol and others, just worked out that, that you would have to do it on an industrial scale.

But that’s not what I’m about, but that’s just the idea of it.

For more information about Michael Landy and his work visit Thomas Dane Gallery in London

www.thomasdanegallery.com/artists/43-michael-landy/works/

www.thomasdanegallery.com/artists/43-michael-landy/works/

All pictures are courtesy and copyright of Michael Landy and Thomas Dane Gallery

Michael Landy's "Breaking News" exhibition is heading to Athens check it out at

www.instagram.com/breakingnewsathens/

www.instagram.com/breakingnewsathens/

Michael Landy

Born in London, 1963

Lives and works in London, UK

Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988

Solo Exhibitions

2017

Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece

2016

Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.)

2015

Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio,London, UK

Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany

2014

Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico

2013

20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.)

Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK

2011

Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia

Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK

Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK

2010

Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK

2009

Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France

2008

Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany

2007

Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.)

H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.)

2004

Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.)

2003

Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany

2002

Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK

2001

Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.)

2000

Handjobs (with Gillian Wearing), Approach Gallery, London, UK

1999

Michael Landy at Home, 7 Fashion Street, London, UK

1996

The Making of Scrapheap Services, Waddington Galleries, London, UK (Cat.)

Scrapheap Services, Electric Press Building, Leeds, UK, organised by the Henry Moore Institute; travelled to: Chisenhale Gallery, London, UK (Cat.)

1995

Multiples: Editions from Scrapheap Services, Ridinghouse Editions, London, UK

Scrapheap Services, Tate Gallery, London, UK

1993

Warning Signs, Karsten Schubert, London, UK

1992

Closing Down Sale, Karsten Schubert, London, UK

1991

Appropriations 1-4, Karsten Schubert, London, UK (Cat.)

1990

Market, Building One, London, UK (Cat.)

Galerie Tanja Grunert, Cologne, Germany Studio Marconi, Milan, Italy

1989

Karsten Schubert, London, UK

Sovereign, Projects for the windows of the Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, New York University, New York, USA

Public Collections

Arts Council of England

British Museum, London, UK

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Royal Academy, London, UK

Tate Collection, London, UK

The British Council, UK

The Government Art Collection, UK

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA

Born in London, 1963

Lives and works in London, UK

Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988

Solo Exhibitions

2017

Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece

2016

Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.)

2015

Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio,London, UK

Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany

2014

Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico

2013

20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.)

Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK

2011

Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia

Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK

Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK

2010

Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK

2009

Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France

2008

Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany

2007

Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.)

H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.)

2004

Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK

Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.)

2003

Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany

2002

Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK

2001

Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.)

2000

Handjobs (with Gillian Wearing), Approach Gallery, London, UK

1999

Michael Landy at Home, 7 Fashion Street, London, UK

1996

The Making of Scrapheap Services, Waddington Galleries, London, UK (Cat.)

Scrapheap Services, Electric Press Building, Leeds, UK, organised by the Henry Moore Institute; travelled to: Chisenhale Gallery, London, UK (Cat.)

1995

Multiples: Editions from Scrapheap Services, Ridinghouse Editions, London, UK

Scrapheap Services, Tate Gallery, London, UK

1993

Warning Signs, Karsten Schubert, London, UK

1992

Closing Down Sale, Karsten Schubert, London, UK

1991

Appropriations 1-4, Karsten Schubert, London, UK (Cat.)

1990

Market, Building One, London, UK (Cat.)

Galerie Tanja Grunert, Cologne, Germany Studio Marconi, Milan, Italy

1989

Karsten Schubert, London, UK

Sovereign, Projects for the windows of the Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, New York University, New York, USA

Public Collections

Arts Council of England

British Museum, London, UK

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Royal Academy, London, UK

Tate Collection, London, UK

The British Council, UK

The Government Art Collection, UK

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA