Hrair Sarkissian on Photography, Art, Memory and showcasing the Visibility of the Invisible in an Image

You spent your childhood working in your father’s photographic studio, can you share with us your memories from that time and how much impact do you think that training has had on your career and on your work?

I started to go to the shop when I was really little, I was about 7 or 8 years old. During the summer holidays we didn’t go anywhere else, I went to the shop literally for three month and I used to clean the toilet floor, make the coffee, all these types of things and i did that every year until the time I was 11 or 12 years old.

I learnt how to work just by looking. There was one big machine that used to print 10,000 prints an hour, it was massive and I learnt from observation, I took over this machine and started to teach other employees and the newcomers to the shop how to work, I was then about 12 or 13 years old.

But the love of photography started before that, because I remember my father was subscribed to this French magazine called La photographie, I wouldn’t read it, I was just in love with looking at the photos. I think it has to do also with the pride my father had, he was always trying to push me to take over the family shop and that’s how I became even more and more involved. As for the impact of the shop, for me, I would consider it my studies, it’s where I learnt everything about photography, technical aspects, everything from photography to printing, all these skills. I also learnt about life, how to deal with adults in the shop, all these kinds of things, it was like a proper academy for me.

I learnt how to work just by looking. There was one big machine that used to print 10,000 prints an hour, it was massive and I learnt from observation, I took over this machine and started to teach other employees and the newcomers to the shop how to work, I was then about 12 or 13 years old.

But the love of photography started before that, because I remember my father was subscribed to this French magazine called La photographie, I wouldn’t read it, I was just in love with looking at the photos. I think it has to do also with the pride my father had, he was always trying to push me to take over the family shop and that’s how I became even more and more involved. As for the impact of the shop, for me, I would consider it my studies, it’s where I learnt everything about photography, technical aspects, everything from photography to printing, all these skills. I also learnt about life, how to deal with adults in the shop, all these kinds of things, it was like a proper academy for me.

You have an Armenian background, you were born in Damascus, you’ve lived in the Netherlands and now in London, all these cities and these cultures, what have they each brought you, do you think they’ve each given you a different perspective?

This mixture brought openness to me and to look at things differently.

It opened a lot the way I look and I think about things. It was already a big window for me when I started to travel outside of Syria in the year 2000. Even then, you can imagine how difficult it was, not financially but to go through all the procedure in respect to visas and all that stuff, but I managed to travel and I attended for instance the photography festival in France Arles for seven years. That was a big shock for me, from then on I started to develop and think more about photography, not in a classical way but more about opening up and seeing the possibilities that can be done with this medium.

This mixture brought openness to me and to look at things differently.

It opened a lot the way I look and I think about things. It was already a big window for me when I started to travel outside of Syria in the year 2000. Even then, you can imagine how difficult it was, not financially but to go through all the procedure in respect to visas and all that stuff, but I managed to travel and I attended for instance the photography festival in France Arles for seven years. That was a big shock for me, from then on I started to develop and think more about photography, not in a classical way but more about opening up and seeing the possibilities that can be done with this medium.

Do you mean, the difference that there may be between a photographer and an artist photographer?

This dilemma I think it exists if you are a photographer, whether you are more in the fine art scene or not. It seems like it’s two completely different markets. As photographers, we keep juggling between here or there we don’t know, sometimes we go here and sometimes we go there. But for me, I prefer being in the art scene, because of the diversity of work it can produce, the capability photography has as a means. I use photography as a tool to seek answers to my memories.

This dilemma I think it exists if you are a photographer, whether you are more in the fine art scene or not. It seems like it’s two completely different markets. As photographers, we keep juggling between here or there we don’t know, sometimes we go here and sometimes we go there. But for me, I prefer being in the art scene, because of the diversity of work it can produce, the capability photography has as a means. I use photography as a tool to seek answers to my memories.

I read that you want to rewrite a perspective of history that’s been lost in the world. Through your photos you are telling the story of a lost history, could you tell us a little more about that

In my work until now I try to avoid doing political works but of course whatever you do at the end of the day, people can look at it politically however, I was always interested in my background where I come from, being Syrian and also having Armenian origins. These two aspects are part of my life and represented in my work, and now even being here in London, it’s not a feeling you get rid of easily.

Where is home for you?

Home is where I have a place and a roof on top of my head, that’s for me home.

After all I’ve been through, many events in my life, leaving my home in Syria and now I see how the situation is there, you just really need a place to be safe, then you can call it home.

In my work until now I try to avoid doing political works but of course whatever you do at the end of the day, people can look at it politically however, I was always interested in my background where I come from, being Syrian and also having Armenian origins. These two aspects are part of my life and represented in my work, and now even being here in London, it’s not a feeling you get rid of easily.

Where is home for you?

Home is where I have a place and a roof on top of my head, that’s for me home.

After all I’ve been through, many events in my life, leaving my home in Syria and now I see how the situation is there, you just really need a place to be safe, then you can call it home.

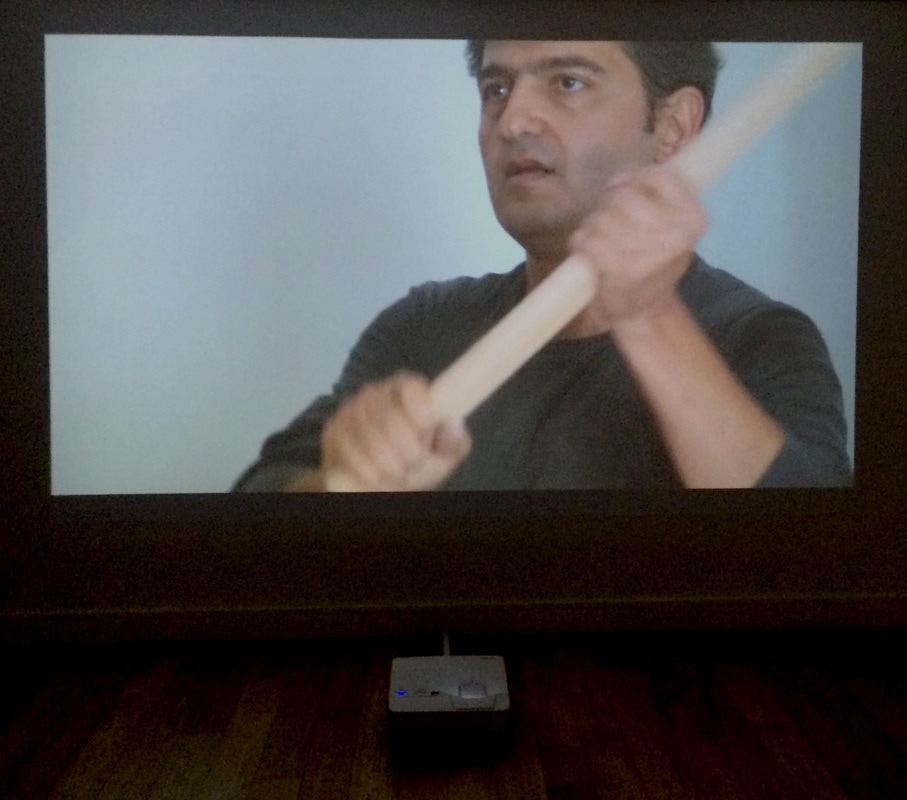

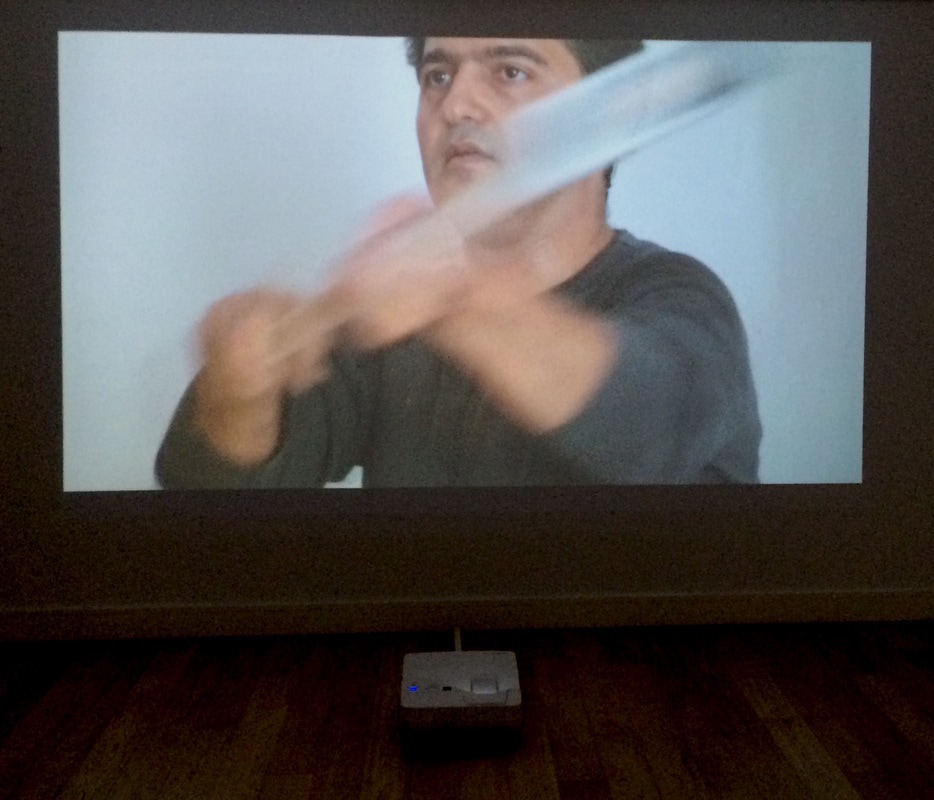

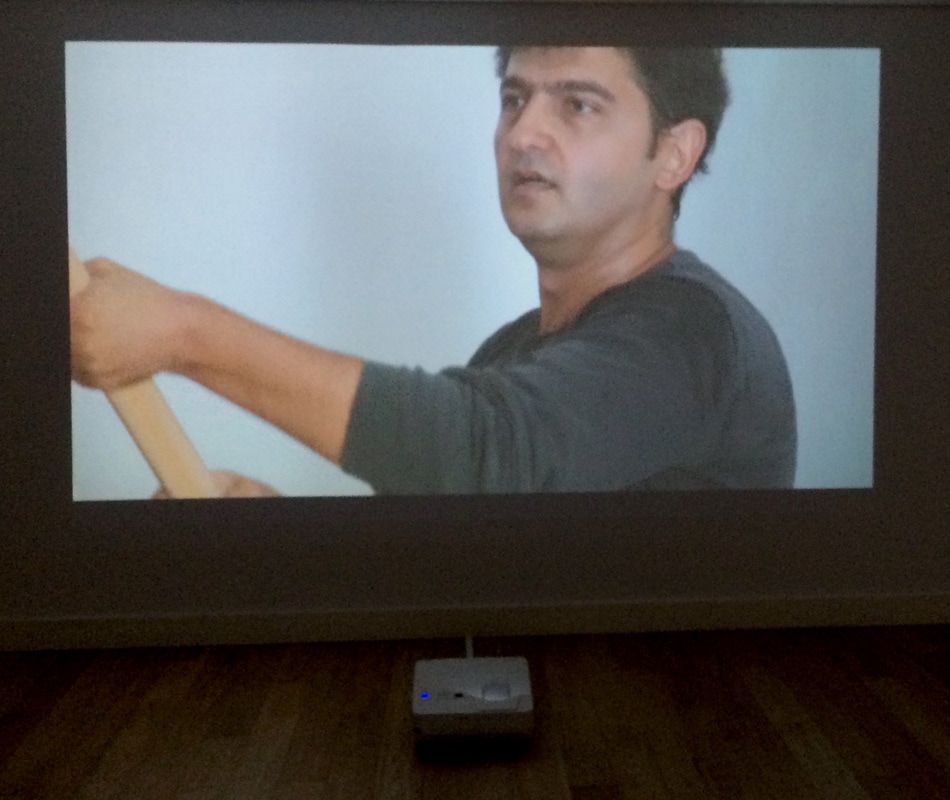

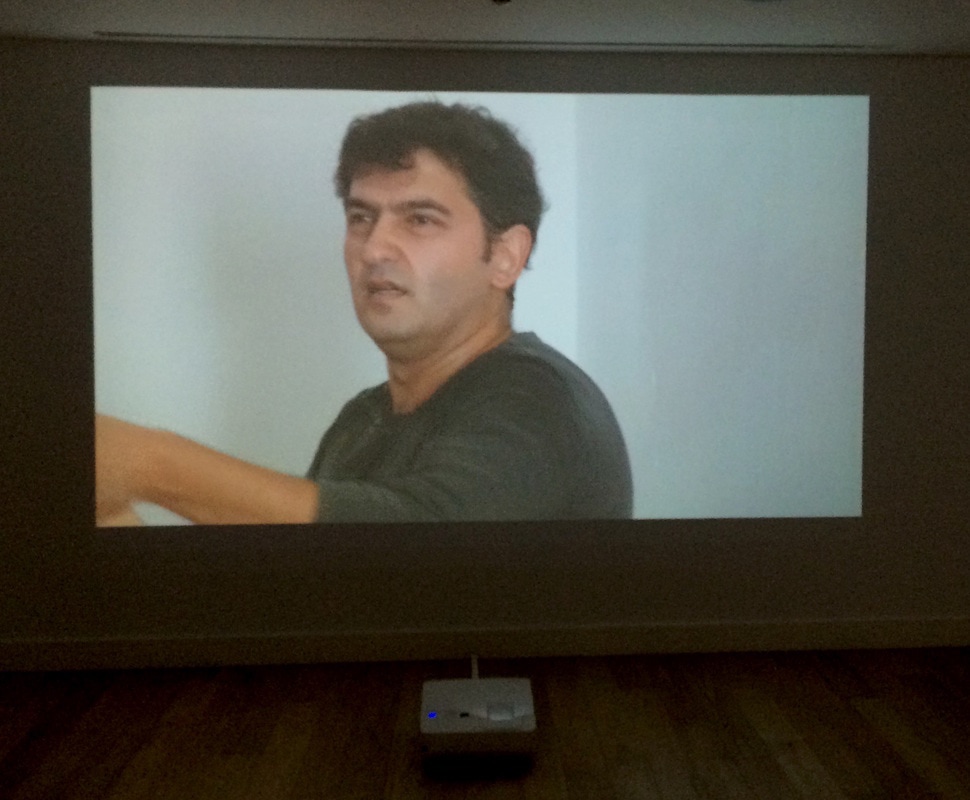

In your artwork 'Homesick', you destroy your house. When I saw it at Mosaic Rooms, there were two projections of the destruction process, one on one side of the room where we could see the destruction and the other on the opposite side of the room where we could hear it. This duality of hearing and seeing was very effective, watching the house, we question who is doing this and watching the video of you hammering, we wonder what you are destroying.

Were you in a way destroying identity away, because sometime it can be a heavy burden, or destroying your memories that may be painful?

Since the war started in Syria I didn’t do any work related to the war directly or indirectly, I refused to. But of course there’s a limit to everything and I was at a point where I really wanted to do something because it is something that’s been constantly on my mind, everyday, the war, the fear, the fear of losing home, the fear of losing memories, the fear of losing my parents because they are still living in the house and it’s the place where I grew up until I left in 2008, and that’s why I came up with this idea of building a model of the apartment building where I used to live and where my parents are still living in now, and because a destruction is something that could happen to anyone of us, not necessarily from war, but it could come from a natural disaster, or a person could be kicked out of their house or for any other different reason. The idea of losing home and losing everything with it could happen to us all.

I built a replica of my home with an architect, and worked with the architect and a builder, it took us two months to build this model, to make it all out of concrete. The dimensions were about 2 metres high, 2.40 the width and 1.70 in depth. I already knew I wanted to destroy it when I built it, even before that. So after we finished, we started to hit it with the sledgehammer and every time we hit it, we took a picture, so each photo represents a hit. It took us about 650 hits to destroy the whole thing and it completely destroyed within 7 hours.

The idea behind it was that I always, until now, have the fear that something will happen to my parents because they are still living in this apartment so it really drives me crazy and at the same time I want to get rid of this image that has been with me all the time. By demolishing this house I thought I might get rid of this fear. But of course, ironically, after I did this project, the house was hit so many times and the windows were completely trashed.

Were you in a way destroying identity away, because sometime it can be a heavy burden, or destroying your memories that may be painful?

Since the war started in Syria I didn’t do any work related to the war directly or indirectly, I refused to. But of course there’s a limit to everything and I was at a point where I really wanted to do something because it is something that’s been constantly on my mind, everyday, the war, the fear, the fear of losing home, the fear of losing memories, the fear of losing my parents because they are still living in the house and it’s the place where I grew up until I left in 2008, and that’s why I came up with this idea of building a model of the apartment building where I used to live and where my parents are still living in now, and because a destruction is something that could happen to anyone of us, not necessarily from war, but it could come from a natural disaster, or a person could be kicked out of their house or for any other different reason. The idea of losing home and losing everything with it could happen to us all.

I built a replica of my home with an architect, and worked with the architect and a builder, it took us two months to build this model, to make it all out of concrete. The dimensions were about 2 metres high, 2.40 the width and 1.70 in depth. I already knew I wanted to destroy it when I built it, even before that. So after we finished, we started to hit it with the sledgehammer and every time we hit it, we took a picture, so each photo represents a hit. It took us about 650 hits to destroy the whole thing and it completely destroyed within 7 hours.

The idea behind it was that I always, until now, have the fear that something will happen to my parents because they are still living in this apartment so it really drives me crazy and at the same time I want to get rid of this image that has been with me all the time. By demolishing this house I thought I might get rid of this fear. But of course, ironically, after I did this project, the house was hit so many times and the windows were completely trashed.

‘Homesick’ (2014) by Hrair Sarkissian Two channel video, 11 min, 7min, Inkjet prints 150 x 190cm

‘Homesick’ (2014) by Hrair Sarkissian Two channel video, 11 min, 7min, Inkjet prints 150 x 190cm

And was it one of the only times that a form of action is taking place in your work?

I wanted to show literally how the effect of demolishing your own house would be and what it feels like, I think that was the main idea. Because with photography, of course you can show that, but it would be really like showing 650 images on the wall of this process and that’s not going to bring any emotions to the viewer. That’s why for the first time I wanted to use moving images out of stills.

I wanted to show literally how the effect of demolishing your own house would be and what it feels like, I think that was the main idea. Because with photography, of course you can show that, but it would be really like showing 650 images on the wall of this process and that’s not going to bring any emotions to the viewer. That’s why for the first time I wanted to use moving images out of stills.

In most of your work, there’s stillness in the photography, whatever the subject even in the artwork 'Execution Squares'.

It’s surprisingly calming

Disturbing calming

Yes disturbing calming

There’s like a silence as well felt in your images. And I don’t know if it is the silence that sometimes as people or as a society we may have on things that happen or have happened in the world.

There’s also the silence there has been and there is about the Armenian Genocide, is that something that is at the back of your mind when you produce an artwork or does it depend on each work?

I think it depends, the silence felt in the images comes from the many issues and different subjects I try to touch upon.

In most of these cases it’s about the visibility of the invisible. Such as in the artwork 'Execution Squares', on the one hand these images show that even without the hanged corpses, these bodies they still exist there somehow, and on the other hand as there are no bodies in the images, photography can try to erase the incident from a memory.

These photos were taken in Syria at 4:30 in the morning and that's the time when they execute criminals in the square and imagine how quiet and calm the square would be at that time, this is one of the aspects that I wanted to bring onto the image.

I think it also reflects somehow how I feel inside, it’s like there’s this quietness which also comes from inside of me, because I don’t like to show images that are really angry, I cannot, because I cannot look at that, so I cannot also take such pictures. I try to use silence also as a tool to bring the viewer closer to the image rather than having these aggressive or direct images that may push people away.

It’s surprisingly calming

Disturbing calming

Yes disturbing calming

There’s like a silence as well felt in your images. And I don’t know if it is the silence that sometimes as people or as a society we may have on things that happen or have happened in the world.

There’s also the silence there has been and there is about the Armenian Genocide, is that something that is at the back of your mind when you produce an artwork or does it depend on each work?

I think it depends, the silence felt in the images comes from the many issues and different subjects I try to touch upon.

In most of these cases it’s about the visibility of the invisible. Such as in the artwork 'Execution Squares', on the one hand these images show that even without the hanged corpses, these bodies they still exist there somehow, and on the other hand as there are no bodies in the images, photography can try to erase the incident from a memory.

These photos were taken in Syria at 4:30 in the morning and that's the time when they execute criminals in the square and imagine how quiet and calm the square would be at that time, this is one of the aspects that I wanted to bring onto the image.

I think it also reflects somehow how I feel inside, it’s like there’s this quietness which also comes from inside of me, because I don’t like to show images that are really angry, I cannot, because I cannot look at that, so I cannot also take such pictures. I try to use silence also as a tool to bring the viewer closer to the image rather than having these aggressive or direct images that may push people away.

I also did read that you said, when you were a little boy, I think 12 years old, that you saw executions

Yes the executions, that’s where the idea for the artwork came from. The memory of this and seeing these bodies on the way to school. It was 6:00 or 6:30 in the morning, I was on the school bus, we were standing which meant I was on the same eye height level with these hanged bodies and their eyes were open, so for me it was quite shocking to see that. This was the first time I encountered a dead body. It was shocking and I keep seeing these bodies always, and this is something I wanted to touch upon, that all of us, I mean in Syria that we all have been through this.

With your artwork 'Front Line', it’s a presentation of history, without any judgement, you are just presenting it to the viewer, is that what you are trying to do with all or most of your work?

Yes because some of these works, they are related to history. Some people may not know about a specific history so it would I think, be interesting to look at the image for that, and i think also maybe add their own story to it.

The type of quietness found in the artworks, a person may keep with them in their mind and so take the image's perspective with them.

Yes the executions, that’s where the idea for the artwork came from. The memory of this and seeing these bodies on the way to school. It was 6:00 or 6:30 in the morning, I was on the school bus, we were standing which meant I was on the same eye height level with these hanged bodies and their eyes were open, so for me it was quite shocking to see that. This was the first time I encountered a dead body. It was shocking and I keep seeing these bodies always, and this is something I wanted to touch upon, that all of us, I mean in Syria that we all have been through this.

With your artwork 'Front Line', it’s a presentation of history, without any judgement, you are just presenting it to the viewer, is that what you are trying to do with all or most of your work?

Yes because some of these works, they are related to history. Some people may not know about a specific history so it would I think, be interesting to look at the image for that, and i think also maybe add their own story to it.

The type of quietness found in the artworks, a person may keep with them in their mind and so take the image's perspective with them.

Front Line (2007), a series of photographs of Karabakh, a self proclaimed independent Republic between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which borders have shifted through the centuries, leaving around a million Armenian’s and Azeri’s displaced. Archival inkjet prints, 100 x 150 cm Photographs printed on perspex (acrylic glass), 25 x 25 x 10 cm

How much power do you think art holds in that case?

I think it does have a power but I don’t think it has a direction, because it depends on the audience too, but it does definitely cause effect.

Do you think maybe it holds more power for a perspective of history more than for the present. As in, in the future we can look back and see a perspective of history that will always live on in works of art

No even in the present it reflects power, even if we talk about the level of for instance photojournalism, the images of the Syrian-Kurdish boy, Aylan Kurdi on the beach, I mean this image did effect.

Yes and It will keep on doing so

So do you think the role of an artist is to highlight what’s going on in society or to reflect one’s personal journey?

I think it depends on the artist, how much he or she is involved. I mean if you look at the artists in the Middle East, they are basically, most of them involved in their work with the political situation of the region, whilst if you look for instance to the Netherlands, you see artists that are dealing with shapes and figures. I think it depends on the situation.

How for you does that affect your work, because you’ve been around both of these influences you mention

It did not affect me, I mean it opened me up on a certain level but it did not affect how I see and deal with things.

I kind of don’t get drawn easily with art figures and shapes, I like to see things that really shake me, move something inside me. It’s not something negative, it’s more that I have to relate and feel an emotion.

You deal a lot with the concept of memory, do you think about the concept for your work, is it a purposeful thought process you go through, or is it just elements of your childhood or your journey that come to you as you work?

I mean most of the time, it comes back, some of these memories they come back. Also we’ve been forced to keep it engraved in our memory because it all relates to the Armenian Genocide, because when you are living in Syria and you are a minority you have to be attached to these stories as it represents and is a structure of your identity within this bigger community and this is how our identity of being Armenian is shaped. The Genocide and the story of the Genocide have a big role in how we build up and for some it’s good and for some it’s also bad because they keep mourning the Genocide without doing anything to deal with it during their life, sadly it is the case.

The parallels with identity and memory, does it go back and forth in your work?

I don’t want to emphasise about identity because it’s something we are born with and forced also upon us, I mean I didn’t choose my identity, nobody does, but I think for me, my work is more the stories, and the moments that I've lived and how they come back again and that makes me think and makes the work about these issues rather than only emphasising on identity. The memory of these stories it’s kind of the fundamental structure in my work that I really lean on.

Is there one element that goes across all your work?

The silence.

I don’t do it on purpose but somehow it is the journey I went through that’s in my work. It’s become something really obvious in my work that the visibility of the invisible becomes something physical that you really want to touch the work.

I think also one element i try to do is engage the viewer into looking at what lies behind the image.

What lies behind something reminds me of when I learnt about the Lisa Wedeen theory 'As if', on how people in Syria 'acted as if' they believed in the propaganda imposed on them, when in fact most didn't, and so i guess this can parallel the notion of memory, in general a memory of a different political way can be intact even if there appears to be a social amnesia.

Many people in this world cannot say anything, cannot talk about politics, the level of fear there is in certain countries in the world is immense. I remember the First time I went to France and people used to talk about the president, I was worried, I was like, is there someone listening to me, I think that’s something inside us.

I think it does have a power but I don’t think it has a direction, because it depends on the audience too, but it does definitely cause effect.

Do you think maybe it holds more power for a perspective of history more than for the present. As in, in the future we can look back and see a perspective of history that will always live on in works of art

No even in the present it reflects power, even if we talk about the level of for instance photojournalism, the images of the Syrian-Kurdish boy, Aylan Kurdi on the beach, I mean this image did effect.

Yes and It will keep on doing so

So do you think the role of an artist is to highlight what’s going on in society or to reflect one’s personal journey?

I think it depends on the artist, how much he or she is involved. I mean if you look at the artists in the Middle East, they are basically, most of them involved in their work with the political situation of the region, whilst if you look for instance to the Netherlands, you see artists that are dealing with shapes and figures. I think it depends on the situation.

How for you does that affect your work, because you’ve been around both of these influences you mention

It did not affect me, I mean it opened me up on a certain level but it did not affect how I see and deal with things.

I kind of don’t get drawn easily with art figures and shapes, I like to see things that really shake me, move something inside me. It’s not something negative, it’s more that I have to relate and feel an emotion.

You deal a lot with the concept of memory, do you think about the concept for your work, is it a purposeful thought process you go through, or is it just elements of your childhood or your journey that come to you as you work?

I mean most of the time, it comes back, some of these memories they come back. Also we’ve been forced to keep it engraved in our memory because it all relates to the Armenian Genocide, because when you are living in Syria and you are a minority you have to be attached to these stories as it represents and is a structure of your identity within this bigger community and this is how our identity of being Armenian is shaped. The Genocide and the story of the Genocide have a big role in how we build up and for some it’s good and for some it’s also bad because they keep mourning the Genocide without doing anything to deal with it during their life, sadly it is the case.

The parallels with identity and memory, does it go back and forth in your work?

I don’t want to emphasise about identity because it’s something we are born with and forced also upon us, I mean I didn’t choose my identity, nobody does, but I think for me, my work is more the stories, and the moments that I've lived and how they come back again and that makes me think and makes the work about these issues rather than only emphasising on identity. The memory of these stories it’s kind of the fundamental structure in my work that I really lean on.

Is there one element that goes across all your work?

The silence.

I don’t do it on purpose but somehow it is the journey I went through that’s in my work. It’s become something really obvious in my work that the visibility of the invisible becomes something physical that you really want to touch the work.

I think also one element i try to do is engage the viewer into looking at what lies behind the image.

What lies behind something reminds me of when I learnt about the Lisa Wedeen theory 'As if', on how people in Syria 'acted as if' they believed in the propaganda imposed on them, when in fact most didn't, and so i guess this can parallel the notion of memory, in general a memory of a different political way can be intact even if there appears to be a social amnesia.

Many people in this world cannot say anything, cannot talk about politics, the level of fear there is in certain countries in the world is immense. I remember the First time I went to France and people used to talk about the president, I was worried, I was like, is there someone listening to me, I think that’s something inside us.

How did you feel doing your artwork 'City Fabrics', because I think I read somewhere that you said that Yerevan is like an imaginary Homeland

Yes because for us it is. Armenia our Motherland or Homeland, I don’t know what I call it anymore, it is imaginary, Armenia for us it’s the country that we will go back to one day but all in the imagination because I don’t think anyone wants to go back and live there, because the situation there is not better than how it was for instance in Syria, not now how it is during the war, but before the war, I would prefer to live in Syria. But we always lived through historical facts, historical stories, that was the connection between us and Armenia, always historical things and also the pride. Being a proud Armenian that we come from this story, we come from this land.

That was for me the contradiction, comparing all this in my imagination with the current situation in Armenia now. There are only 3 million people left, all the youth are leaving, emigrating or already emigrated and they are still emigrating, so the country is collapsing and that’s why I found it quite an interesting relationship showing these modern buildings with these fabrics but with wrinkles because it is wrinkling and this street portrayed, it was one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Yerevan from 1920. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the mafia then came and destroyed all the old houses, as they came to build new buildings to sell them to the people of the diaspora but of course nobody came and bought as they were so expensive.

I would never buy an apartment in Yerevan because I am already living in an apartment why would I buy another apartment, why buy a similar construct there. The project failed and that’s why they were covered with large fabrics with images of the buildings on them.

Yes because for us it is. Armenia our Motherland or Homeland, I don’t know what I call it anymore, it is imaginary, Armenia for us it’s the country that we will go back to one day but all in the imagination because I don’t think anyone wants to go back and live there, because the situation there is not better than how it was for instance in Syria, not now how it is during the war, but before the war, I would prefer to live in Syria. But we always lived through historical facts, historical stories, that was the connection between us and Armenia, always historical things and also the pride. Being a proud Armenian that we come from this story, we come from this land.

That was for me the contradiction, comparing all this in my imagination with the current situation in Armenia now. There are only 3 million people left, all the youth are leaving, emigrating or already emigrated and they are still emigrating, so the country is collapsing and that’s why I found it quite an interesting relationship showing these modern buildings with these fabrics but with wrinkles because it is wrinkling and this street portrayed, it was one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Yerevan from 1920. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the mafia then came and destroyed all the old houses, as they came to build new buildings to sell them to the people of the diaspora but of course nobody came and bought as they were so expensive.

I would never buy an apartment in Yerevan because I am already living in an apartment why would I buy another apartment, why buy a similar construct there. The project failed and that’s why they were covered with large fabrics with images of the buildings on them.

Do you feel like coming from a diaspora, that it gives you a different perspective? Like you are neither here nor there, maybe you are accepted and not accepted at the same time, and that there may be a feeling of guilt of not being in your mother country all the time and yet why would you be or have to be

I think being accepted or not being accepted there are always issues even if you are or not from the diaspora, people will find something that they cling onto and say ah you don’t belong here or you don’t speak the language or your name is nuts or you didn’t live here, any of these things.

Already when I was in Syria I was part of the diaspora, coming to London or leaving Syria again I don’t think anything has changed for me with this idea of living in diaspora.

Maybe we are all in a constant diaspora

Probably

I think being accepted or not being accepted there are always issues even if you are or not from the diaspora, people will find something that they cling onto and say ah you don’t belong here or you don’t speak the language or your name is nuts or you didn’t live here, any of these things.

Already when I was in Syria I was part of the diaspora, coming to London or leaving Syria again I don’t think anything has changed for me with this idea of living in diaspora.

Maybe we are all in a constant diaspora

Probably

The memory of your life stories in your work are so profound yet they are also aesthetically really beautiful

I think that comes from my father

Do you mean how he trained you?

I have to say my father did not train me because he didn’t have time. I was always stealing moments from him, I was always sitting next to him and watching and that’s how I learnt

He did not have time, he also did not have the patience, he might say something once and then that’s it. But I had to learn just by observing and it’s the same with the images and how I frame and structure them, it all comes from him.

Maybe that’s the best way, because in photography you have to observe, so in a way i guess you were also learning to observe

I would consider that the base, my base. It’s the root of the tree.

Also if I kept only leaning on aesthetics, my work would not have developed to where it is today. For me, i had a deep need to relay stories.

I think that comes from my father

Do you mean how he trained you?

I have to say my father did not train me because he didn’t have time. I was always stealing moments from him, I was always sitting next to him and watching and that’s how I learnt

He did not have time, he also did not have the patience, he might say something once and then that’s it. But I had to learn just by observing and it’s the same with the images and how I frame and structure them, it all comes from him.

Maybe that’s the best way, because in photography you have to observe, so in a way i guess you were also learning to observe

I would consider that the base, my base. It’s the root of the tree.

Also if I kept only leaning on aesthetics, my work would not have developed to where it is today. For me, i had a deep need to relay stories.

How do you feel today about the fact that now we all have Iphones, we all take photos, and there are filters and crops we can use and do easily, how do you feel about this?

I don’t think about it. I don’t have a digital camera. I still work with my old camera, a Canham camera, old fashioned, where you have the black cloth and you just hide underneath. I don’t make a lot of photos, I’m not the one who carries around a camera and walks around and takes a photo. It’s always researched based, I prepare everything and then go and shoot and come back.

And I don’t photograph people, rarely.

How come?

I try to avoid it, because I don’t feel comfortable doing so. Even when I was at my father’s shop even for commercial reasons, I mean I did shoot ID photos which were quite straightforward, but if someone wanted their portrait for their family, I would ask my father to do it, I would try to escape because I just couldn’t deal with that.

Was there a particular reason?

I think it’s psychological, there is no particular reason, no. I feel more at ease when I am in a space where there is no one, it’s more the feeling of there are no rules, no restrictions, no one is looking at me. I cannot take this quick shot and escape, like stealing something.

With the process of how I take photos, it’s really quite present, because I come with this huge tripod and this massive camera and just place it and stand behind it, just to let everyone know I am there, I’m not stealing.

I don’t think about it. I don’t have a digital camera. I still work with my old camera, a Canham camera, old fashioned, where you have the black cloth and you just hide underneath. I don’t make a lot of photos, I’m not the one who carries around a camera and walks around and takes a photo. It’s always researched based, I prepare everything and then go and shoot and come back.

And I don’t photograph people, rarely.

How come?

I try to avoid it, because I don’t feel comfortable doing so. Even when I was at my father’s shop even for commercial reasons, I mean I did shoot ID photos which were quite straightforward, but if someone wanted their portrait for their family, I would ask my father to do it, I would try to escape because I just couldn’t deal with that.

Was there a particular reason?

I think it’s psychological, there is no particular reason, no. I feel more at ease when I am in a space where there is no one, it’s more the feeling of there are no rules, no restrictions, no one is looking at me. I cannot take this quick shot and escape, like stealing something.

With the process of how I take photos, it’s really quite present, because I come with this huge tripod and this massive camera and just place it and stand behind it, just to let everyone know I am there, I’m not stealing.

How would you define what an artist is?

Privileged, maybe it’s a way of living

Or a way of seeing?

A way of seeing, yes and telling.

It’s not easy, really it’s very difficult to be an artist, and I think that’s also part of the package let’s say.

Privileged, maybe it’s a way of living

Or a way of seeing?

A way of seeing, yes and telling.

It’s not easy, really it’s very difficult to be an artist, and I think that’s also part of the package let’s say.

How was the process of doing your artwork 'Istory'?

It was quite frustrating. It was made possible with the big help of SALT foundation. They provided me with the recommendation letter stating that I was doing an art project and they also always contacted, but the thing that was always irritating for me was that whenever I went to the institutions to work and showed the letter, of course my name is quite obviously an Armenian name, whenever they read the name, they would start to look at me with suspicion, as if they were thinking, are you going to find something.

So many institutions refused to give me access and some of them did not allow me to go into their archive room or where they keep all the National Archives where they hold all the official documents of the Armenian Genocide during the Ottoman Empire which was not open to the public until now. The director brought someone who can speak Arabic to translate everything I was saying and eventually the director said no I cannot give you permission to photograph the room, (not the documents, I wasn’t asking for the documents), and he only let me photograph the reading room which was an empty room and I accepted. There were only shelves, some were empty shelves and cupboards and so I accepted. It was very frustrating to do this project. There was always this fear of just being circled, with an entourage, sometimes even with guards, they wanted to see what I was doing and they wanted to check the photographs as well, so it was not an easy process for me, I was quite happy to finish it, I just wanted to leave as soon as possible and eventually we showed the work at SALT.

It was quite frustrating. It was made possible with the big help of SALT foundation. They provided me with the recommendation letter stating that I was doing an art project and they also always contacted, but the thing that was always irritating for me was that whenever I went to the institutions to work and showed the letter, of course my name is quite obviously an Armenian name, whenever they read the name, they would start to look at me with suspicion, as if they were thinking, are you going to find something.

So many institutions refused to give me access and some of them did not allow me to go into their archive room or where they keep all the National Archives where they hold all the official documents of the Armenian Genocide during the Ottoman Empire which was not open to the public until now. The director brought someone who can speak Arabic to translate everything I was saying and eventually the director said no I cannot give you permission to photograph the room, (not the documents, I wasn’t asking for the documents), and he only let me photograph the reading room which was an empty room and I accepted. There were only shelves, some were empty shelves and cupboards and so I accepted. It was very frustrating to do this project. There was always this fear of just being circled, with an entourage, sometimes even with guards, they wanted to see what I was doing and they wanted to check the photographs as well, so it was not an easy process for me, I was quite happy to finish it, I just wanted to leave as soon as possible and eventually we showed the work at SALT.

Istory: In 2010 Hrair Sarkissian spent two months in Istanbul documenting the history sections of various semi-private and public libraries and archives in the city, from the Archeological Museum and Topkapi Palace Libraries to the Atatürk Library at Taksim, the Ottoman Archives in the Government Office and Garanti Bank’s Ottoman Bank Archive. While the specific content of the archives remain concealed, Sarkissian’s photographs captures the rows of information that there is. Archival inkjet prints, 150 x 190 cm

You’re latest work is 'Horizon', you depicted the shortest route for a refugee to take from Kaş on the southwestern Turkish shore, across the Mycale Strait, to the island of Megisti on the edge of southeastern Greece

Part of it is just feeling handicapped or paralyzed of not being able to do anything. I mean all of us in general not being able to do anything about the whole issue, that’s why I wanted to also film it from above with a drone, that we could just go passed what is happening, but they are there in the water. And also to show how close it all is.

But actually, that’s not even the greatest difficulty they face, the second difficulty is once people are close to the other side of the land, the hardship restarts, it’s an even longer journey than this 1.2 kilometres i depict.

Part of it is just feeling handicapped or paralyzed of not being able to do anything. I mean all of us in general not being able to do anything about the whole issue, that’s why I wanted to also film it from above with a drone, that we could just go passed what is happening, but they are there in the water. And also to show how close it all is.

But actually, that’s not even the greatest difficulty they face, the second difficulty is once people are close to the other side of the land, the hardship restarts, it’s an even longer journey than this 1.2 kilometres i depict.

Are you going more into film?

No, I love photography because I know how to deal with images and that’s what I feel.

I don’t feel the same way when I work with video, I feel completely handicapped, because I don’t know much about video so I have to ask someone, another technician to help with the project, which I don’t like the idea of, I want to be there, I want to do the thing.

What is next for you?

I have a solo exhibition at Sursock Museum in Beirut Lebanon from 7th July, on show will be the artworks 'Homesick' and 'Horizon'.

No, I love photography because I know how to deal with images and that’s what I feel.

I don’t feel the same way when I work with video, I feel completely handicapped, because I don’t know much about video so I have to ask someone, another technician to help with the project, which I don’t like the idea of, I want to be there, I want to do the thing.

What is next for you?

I have a solo exhibition at Sursock Museum in Beirut Lebanon from 7th July, on show will be the artworks 'Homesick' and 'Horizon'.

Hrair Sarkissian is a photographer. Born and raised in Damascus, he earned his foundational training at his father’s photographic studio, where he spent all his childhood vacations and where he worked full-time for twelve years after high school. In 2010 he completed a BFA in Photography at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam and won the Steenbergen Stipendium, Netherlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam. In 2012 he won the Abraaj Group Art Prize, Dubai. His works form part of collections at the Tate Modern, London, Mori Museum, Tokyo, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Modena, Modena, Italy, Fondazione Cari Spezia, La Spezia, Italy, Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah, The Khalid Shoman Collection, Amman and The Farjam Collection, Dubai.

He lives and works in London since 2011.

He lives and works in London since 2011.

|

|

|